To say that I have been obsessing over this lately would be an understatement, as my last eureka! moment regarding the MS I was actively querying was that the world I thought I had a handle on (I have charts! and graphs! and color-coded notecards! and MAPS!) was not actually complete. Also that I have to restructure the first ten chapters and remove an entire sub-plot, but that's a different matter.

So, yeah, I've been obsessed with world building. And about the time I really do not want to admit it is going to take before I am satisfied enough to start querying again. I am feeling not unlike this:

… only I already have a golden goose, so at least I don't have *that* to complain about.

(Fun fact: I looked up Veruca Salt in Google images, and the dozenth or so picture was one that I took during our Wonka Hike at Hometown Europe in 2009, that I had put on that year's Village Page! Yes, I am pretty much famous)

So obviously, owing to the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon*, the two for-fun books I managed to get through last week were both epic fantasies (tick) with deep mythologies (double tick) that had to introduce remarkably enormous worlds in the span of 350ish pages. This fact was made all the more obvious as one of the books pulled the world building off with ease, while the other was so patronizingly dull that I groaned out loud probably two dozen times.

So of course I wanted to compare them.

[Orson Scott Card, Finnikin of the Rock, and a Damn Interesting follow-up to that asterisk after the jump]

Okay. In Corner #1 we have…

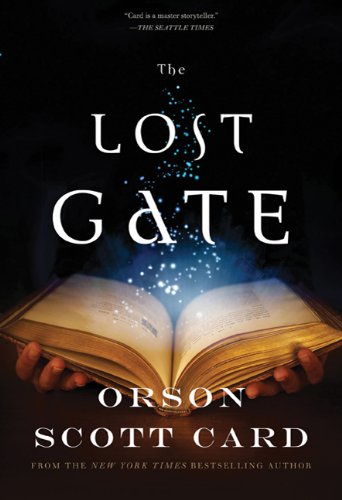

The Lost Gate, by Orson Scott Card

Card's newest book, The Lost Gate, is fantastic. Wonderfully compelling, amazingly fresh (given the material he tackled), effortlessly clever – all that.

And now, in Corner #2 we have…

Finnikin of the Rock, by Melina Marchetta

Unlike The Lost Gate, the world Marchetta creates in Finnikin of the Rock is so monstrously thick that, from page one, all she can have anyone do – the narrator, the characters, whoever – is TELL the reader the backstory, and ploddingly. The world was rich, and the story could have been interesting, but all the WORDS just got in the way of seeing that.

Now, I don't like being critical in a public forum, so I had initially planned to leave the second example anonymous. I mean, I adore, adore Marchetta's Jellicoe Road, so much so that I recommend it to pretty much everyone I talk to, whether they read YA or not. But then I thought, you know why I love Jellicoe Road? Because the world she built – even if it isn't fantasy – was so complex and fascinating and unfolded in such a natural, compelling, completely not-telling way. So there's the rub: I know Marchetta can do this. She's a genius at world building.

So what happened to Finnikin of the Rock?

My guess is time. In the notes that follow The Lost Gate (of course there are notes, he's famous), Orson Scott Card discusses how he first came up with the world of the story in 1977. 1977. He thought of the rules to the magic, made the map of the planet of Westil, wrote all sorts of short stories that took place in that world, and so on. But it wasn't until a couple years ago that he actually felt confident enough to write the story he wanted to tell and have it be good enough.

Also, it doesn't hurt that he has decades of fantasy/sci-fi world building experience under his belt, but still, the takeaway message here is TIME. With all that time to really absorb the world of Westil into his pores, Card was able to tell his story without talking down to the reader, without making his narrator or his characters explain the backstory rather than move forward on their journey and let pieces of the history fall into the reader's laps as they went, no explanation necessary.

Marchetta, on the other hand, is new to fantasy, and does not have decades of a career behind her. There is no way, of course, for me to know how long Finnikin's world had been stewing in her creative centers before she sat down to write it, but at the very least we are safe in assuming NOT thirty-five years. Almost certainly not ten, and maybe not even five. And since I know that she can absolutely let a story unwind and drop nuggets of backstory into the reader's hands only when it is necessary, and without any pedantic telling, I can only imagine that a lack of time led to Finnikin being so much less than it should have been.

Now, I don't think that there is any magic number to how long a world has to sit in the imagination before it is ready to be presented. Sometimes an idea is so pure and whole when it comes to you, you don't need any extra time. Sometimes it's complex, and takes forever. Me, I'm working on year three of constructing the right and complete world for my characters, and not letting them monologue their way through the backstory. And it is HARD. And it will just take time.

Time. Sigh.

Guess I will just have to entertain myself with my golden goose until then…

(and no! I didn't forget! *big fatty asterisk, the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon is when you learn something for the first time, or think of something unique, and then it suddenly seems to pop up everywhere you turn. It's unsettling.)

No comments:

Post a Comment